05: Fashion and The Gothic

Victorian Mourning, Subculture, Alexander McQueen, Galliano, and Gaultier and the Gothic tradition

Photo from The Hunger. In 1979, Bauhaus released their first single, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” in reference to the late actor Bela Lugosi who starred as Count Dracula in the 1931 adaption of Bram Stoker’s novel -- the same song often credited as the beginning of goth music. The song’s lyrics directly referenced the film: “Bela Lugosi’s dead, the bats have left the bell tower, the victims have been bled, red velvet lines the black box.” Just as Bram Stoker’s 1889 novel Dracula and the early 20th-century film adaptions popularized the vampire in the modern imagination, Bauhaus’ first single is credited as the true beginning of gothic rock. Four years later, in 1983, Bauhaus fittingly performed the song in a New York nightclub in the opening of the cult-followed vampire horror film The Hunger starring none other than David Bowie, Catherine Deneuve, and Susan Sarandon.

My Mom used to have a blue airtight box of her old clothes stacked between one filled with my elementary school art and one filled with her cassettes from high school. I’d sift through the box and my mom would tell me about her days clubbing in Germany, how much she used to spend on her clothes, and the goths that came out at night and hung out under the bridge smoking cigarettes and listening to The Sisters of Mercy. In high school, I’d open the box and find something new to wear each time. I tried to double sock to fit into her English-made Doc Martens (the ones without the yellow stitching), I faithfully wore the green velvet Betsy Johnson dress in 8th grade, and I wore the silver dress two years ago for Halloween when I went as Bella Hadid’s Juul and the black lace suit to dinner -- the same one she allegedly wore to the club in a g-string. The green suede fluevlogs never fit me, nor did the skull-covered derbies, the black 1920s coat, or the red and black Victorian-inspired two-piece.

The box in my Mom’s closet and the stories she’d tell as I dumped its contents onto her bedroom floor was my first exposure to goth. I liked to tell people that my mom used to be goth and she used to have a mohawk and she used to live in Germany and stay out all night clubbing. As I researched for this piece, I saw my Mom and the contents of the box in everything I read and all the images I examined. The box of my Mom’s clothes is a reminder of the perennial nature of both fashion and the gothic. It took me a long time to appreciate it for more than a trove of things to borrow. It is and was an archive of my mother’s youth and remnants of the final years of a European subculture.

While the gothic subculture of the late 1970s and 1980s is the most well-known contemporary manifestation of the gothic, Gothicism has a historic and literary tradition that began long before the rise of the London subculture. The goth subculture was a contemporary manifestation of the gothic, or rather, as Lauren M.E. Goodland and Michael Bibby explain in the introduction to Undead Goth, the goth subculture “launched an ongoing extension and revision of this practice.” They explain, “Goth incorporated elements of pre-subcultural literary, philosophical, and aesthetic traditions within a continuing process of cumulative genealogical construction.” The fashion, too, produced by designers like McQueen, Galliano, and Gaultier among others can be understood as an extension of the Victorian Gothic tradition — one that is in a continuous state of reinvention.

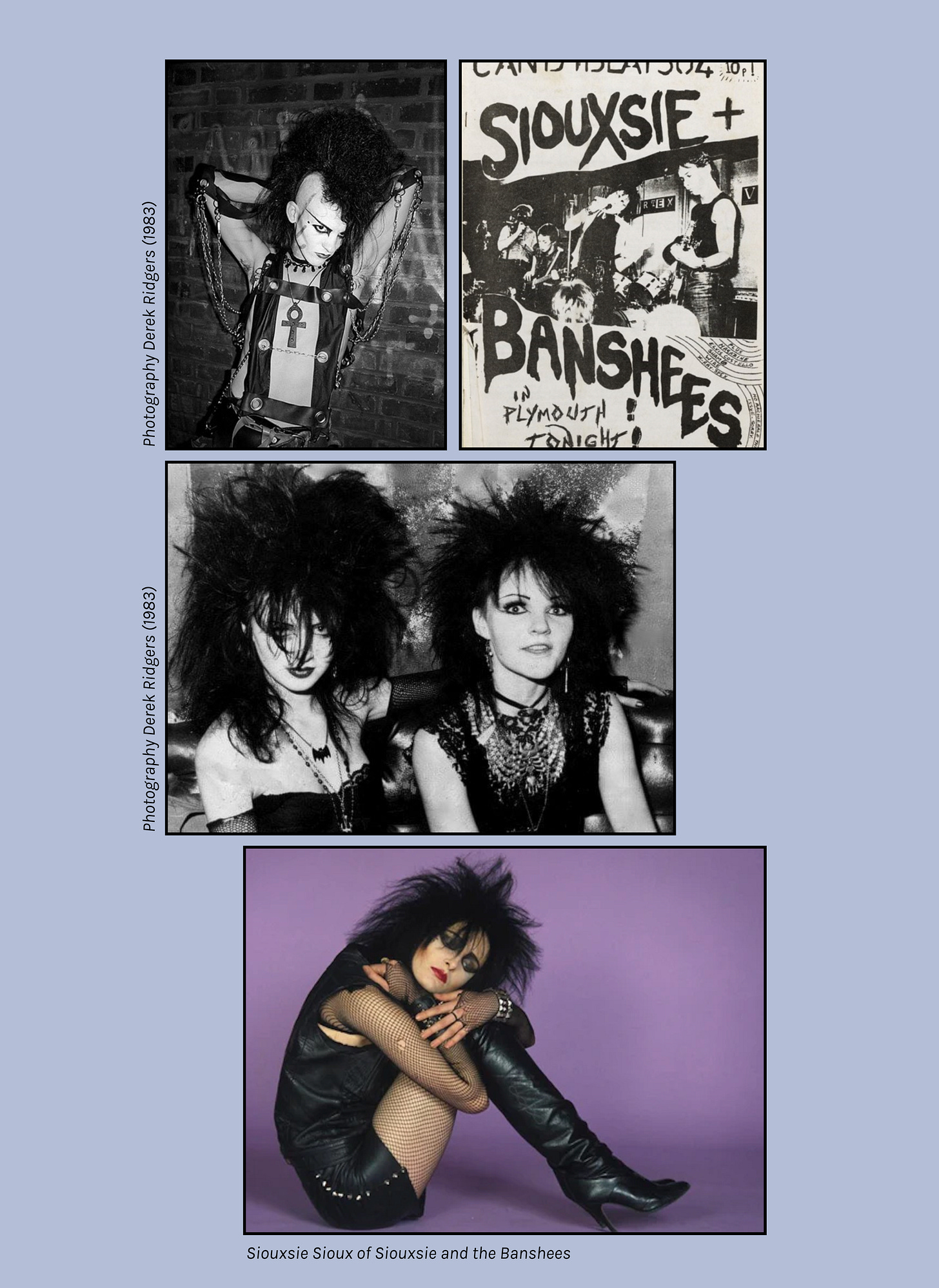

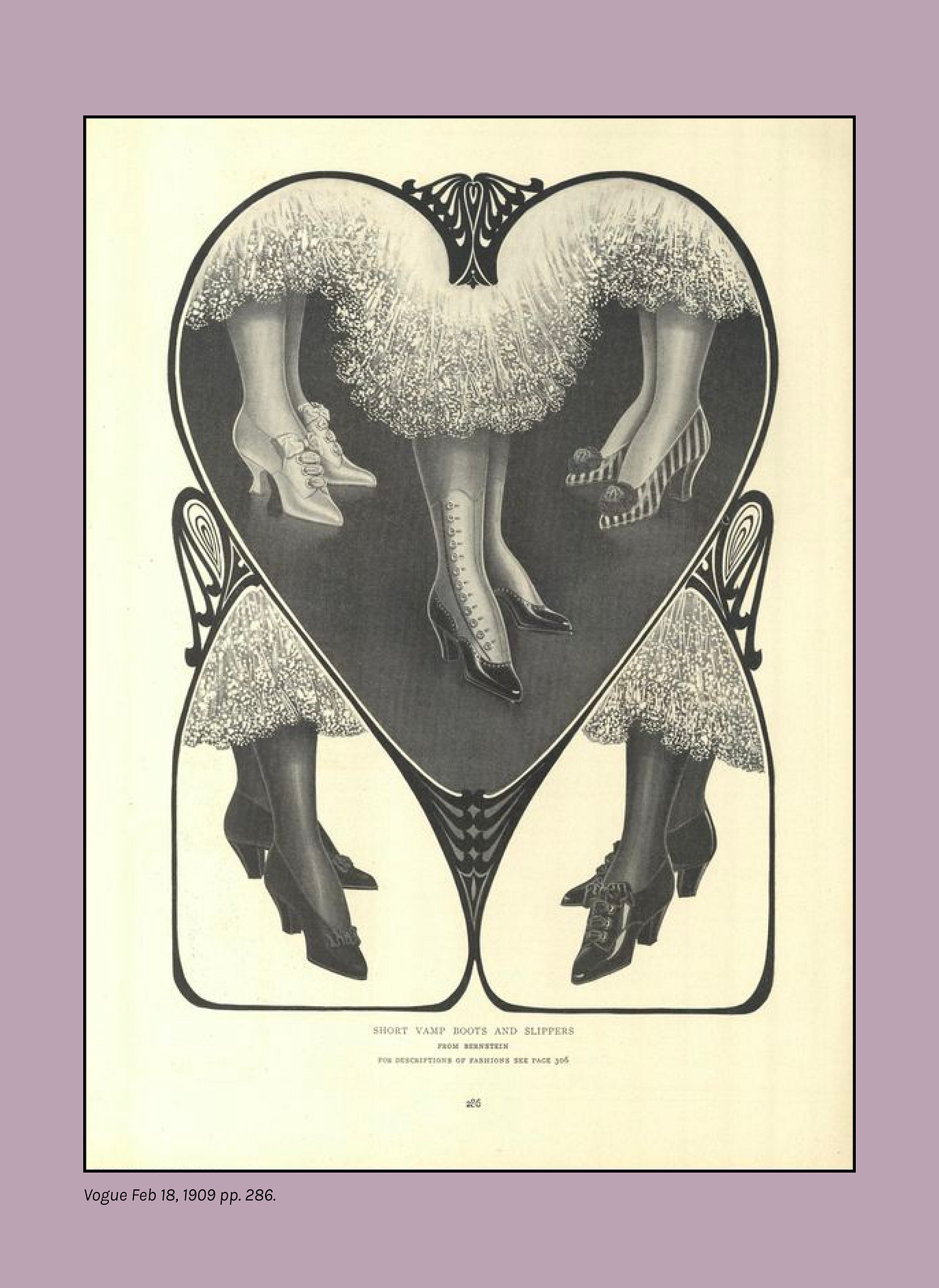

Music played an instrumental part in the emergence of the gothic subculture in the early to mid-1980s, but fashion shaped the subculture's aesthetic identity. As in most subcultures, appearance was a vital expression of belonging. Gothic fashion rejected “normal” or “natural” beauty in favor of an often androgynous and defiant version that rejected patriarchal beauty standards. The fashion of the goth subculture was an amalgamation of styles. As Lauren M.E. Goodland and Michael Bibby explain in the introduction to Undead Goth, "…the goth tendency to embrace gothic literature and art has made the subculture more dialectically engaged with the past than is typical of most youth cultures, providing yet another source of exceptional vitality. The antique and archaic are central to a gothic sensibility, just as death itself is typically perceived as a source of inspiration rather than a terminus." The fashion reflected the subculture's reliance on literary reference and history, goths drew inspiration from the punks before them, horror films, vampires, "oppositional sexual practices including queer, drag, porn, fetish, and b-d/s-m," and the subculture readily borrowed from the Victorian era - corsetry, mourning, veils, lace-up 'vamp' boots, and 'feminine' materials like lace and velvet.

Top: Print (1878), Mourning Dress (1880s), Parasol (1890s) Bottom: Tall Boots (1895), Black Short Boots (1865), Dress by Sara Mayer & A. Morhanger (1889).

The most significant form of gothic reference comes from the Victorian. As Alexandra Warwick articulates in Victorian Gothic, “…Gothic did not die; indeed, in the popular imagination, the Victorian is in many ways the Gothic period, with its elaborate cult of death and mourning, its fascination with ghosts, spiritualism, and the occult, and not least because of the powerful fictional figures of the late century.” Literature, especially 18th and 19th-century literature, has played a vital role in constructing the Gothic in the modern imagination.

The “Female Gothic” novel provides a particularly illuminating lens for understanding both the contemporary problems of Victorian women and the historical use of garments to display ‘private choices’. The term “female gothic” was coined in 1976 by gynocriticist Ellen Moers to describe the work of 18th-century women writers like Ann Radcliffe and Emily and Charlotte Bronte. “Female Gothic” literature engaged heavily with themes of madness, mental illness, the unconscious, and violence against women. In turn, fashion, or rather the choices women made over what they wore, emerged as a symbol of agency. In “Fashion and the Female Gothic”, Amy L. Montz explains, “Sartorial choices are the very definition of the private made public. We get dressed, every day, and our clothing is dependent on where we intend to go. We choose what to wear not only based on the circumstances of our place in the public sphere but also, we choose what to wear; that is to say, it is a private choice, about private taste, revealed publicly on the body.” (748) Like "the female gothic", the goth subculture used sartorial choices to display agency and “private” ideas around oppression and the patriarchy.

Mourning attire also provided women with an opportunity to display their private matters publicly. Due to the constant presence of diseases such as measles, mumps, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and rubella in Victorian England, the threat of death was always looming. After Prince Albert died in December 1861 from typhoid, Queen Victoria entered a period of mourning that lasted the final forty years of her life. She wore a black lace veil and dress for the rest of her life and required all her guests to wear black from head to toe as well. A period of mourning was customary in the Victorian era, and widows were expected to wear black dresses, hats, and heavy black veils for two years following the death of their husbands to symbolize their grief and respect. While etiquette books emphasized the importance of "plain" mourning attire, it became a fashionable form of dress. Even American Vogue discussed and advertised fashionable mourning dresses and veils into the late 1930s. Women in mourning helped make death and grief a common facet of everyday life. The aesthetics of death and grief became an important reference for the goth subculture and goth fashion, often seen paired with religious iconography, lace veils, rhinestone crosses, and rosary beads.

Catherine Spooner wonderfully articulates the pervasive nature of gothic imagery and narratives in all facets of contemporary life in the introduction of her book, Contemporary Gothic, “Gothic texts deal with a variety of themes just as pertinent to contemporary culture as to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Gothic novels first achieved popularity: the legacies of the past and its burdens on the present; the radically provisional or divided nature of the self; the construction of peoples or individuals as monstrous or ‘other’; the preoccupation with bodies that modified, grotesque, or diseased.” She continues, “Gothic has become so pervasive precisely because it is so apposite to the representation of contemporary concerns.” Just as victorian gothic literature reflected social anxieties, the gothic subculture emerged to do the same within the context of the 1970s and 1980s. The fashion that emerged in the 1990s goth resurgence, similarly engaged with contemporary concerns about beauty, mental illness, self and gender.

No designer has so aptly and meaningfully — although often controversially — engaged with the themes of the gothic as the late Alexander McQueen. McQueen’s Spring 1996 collection “The Hunger” was named after and inspired by the same vampire cult classic that inspired the New York-based goth subculture magazine Propaganda — the movie that opened with Bauhaus’ Bela Lugosi’s Dead. McQueen’s Fall 2001 Ready-to-Wear collection titled What-a-Merry-Go-Around opened with models walking around the beloved children’s ride with an array of beige, grey and brown dresses and suits with pointy stilettos. As the show wore on, the looks got darker. One of the models, who wore a black gown dragged a skeleton across the stage at her ankle, death literally at her heel. When the last two models walked around the merry-go-round and off the stage, the show slowed and lights dimmed before revealing a disturbing backdrop of black and orange carnival balloons, massive stuffed animals, discarded children’s toys, and mutilated dolls. The models had ditched their black vampy lipstick and 1920s finger waves for matted clown hair covered in cobwebs and black and white clown makeup. They came to life among the discarded remnants of childhood.

An analysis of any of McQueen's shows reveals a darker historical undertone, but perhaps his most famously disturbing spectacle was his Spring/Summer 2001 show, Voss. The show was staged in a two-way mirrored box, or rather, an asylum with white padded walls. The showgoers took their seats around the mirrored glass box where they stared at their reflection for two hours before the show finally began. When the show began, the audience could watch the models, but the models could not see the audience. The models' heads were wrapped in white bandages. McQueen wanted them to look like they had just undergone a medical procedure. In the center of the padded asylum stood another box. Before the show came to a close, the lights dimmed, and the walls of the dirty glass box fell to the ground and shattered to reveal McQueen's recreation of Joel-Peter Witkin's Sanitarium (1983). A fat naked woman lay in the center, masked and attached to breathing tubes. As the butterflies filled the asylum, the models walked back out for the finale, banging and scraping on the glass walls to get out. Of Voss, Valerie Steele writes, "McQueen's mirrored asylum is a reminder that fashion as a phenomenon inevitably emphasizes surface spectacle and performance. This, too, is a part of the gothic." McQueen engaged less with the aesthetics of the gothic as he did with the ideas of the gothic. Voss engaged both with ideas about spectacle and performance but of madness, sanity, and notions of beauty. From his first show in London in 1993 to his last in Paris in 2010, McQueen coupled intricate craftsmanship with a penchant for spectacle and haunting, often disturbing narrative.

In Gothic: Dark Glamour author Valerie Steele explains, “Gothic fashion, like the gothic novel, tends to be obsessed with the past, often a theatrical, highly artificial version of the past that contrasts dramatically with the perceived banality of contemporary life.” If any designer has made a career out of creating theatrical interpretations of the past it is John Galliano. John Galliano’s Fall/Winter 2001 show is a perfect example of his penchant for theatrics, referential designs, and gothic inspiration. The show was heavily inspired by Montparnasse in the early 20th century which served as the literary and artistic hub of Paris and the birthplace of movements like Surrealism and Dadaism. Montparnasse quickly became a meeting center for artists and writers, all of which were virtually penniless because of the inexpensive rent and thriving cafe culture. The collection references famous “characters” of Montparnasse like Kiki de Montparnasse and Madame Bijoux, an almost mythical personality who spent her days drinking at Bar de La Lune covered in all the pearls she owned. Although nobody really knows, Bijoux is said to have once been an exotic interpretative dancer, a nude actress, a mistress to a wealthy older man, and a muse to a poet. Perhaps her mystery is what Galliano found so enchanting.

The show’s set was a theatrical recreation of the streets of Montparnasse during its time as the hub of bohemian life in Paris. The stage was decorated with fictional street characters, an old woman and several men who lingered among objects of disrepair — moss-covered statues, old Turkish rugs, candlesticks, taxidermy animals, and skeletons in bails of hay. Two of the men lay in a hay-stuffed bed and pined after the models as they walked by.

As usual for a John Galliano show, Pat McGrath did the makeup — pale faces, arched eyebrows, spectacularly elaborate Theda Bara-esque eyeshadow that got darker as the show wore on until it was dripping down the model's wet faces. The looks, too, got darker. The show started with girls in whimsical dresses and coats in shades of red and pink some with contrasting chartreuse tights. And by the end, the girls with wet hair were wearing black 1930s-inspired bias gowns that teetered the line between evening wear and lingerie. Crumpled veils and oversized hats adorned with faux flowers were everywhere — reminiscent of both the extravagant hats of the early 20th century and Victorian mourning veils. When Valerie Steele asked John Galliano what ‘Gothic’ meant to him, he replied, “dark, vampy, mysterious, dangerous — she is edgy and cool. The gothic girl weaves a web, has a sting in her tail, is inspired by black magic and voodoo… She is tantalizing, after dark trouble dresses in the shadows of the night.” (82) John Galliano’s Fall/Winter 2001 show illustrates both Galliano’s own ideas about gothicism and the tensions between public and private life as they relate to gender.

Jean Paul Gaultier, too, has regularly engaged with gothic imagery in his designs. Gaultier’s Spring/Summer 1998 collection combined inspiration from the goth music scene with Frida Kahlo. The collection featured an array of soft long-black dresses paired by with colorful ones inspired by the Mexican artist. The models wore Kahlo-esque unibrows, wept tears of blood, and wore ornate headpieces and religious iconography - oversized cross necklaces and rosary beads.

Just as McQueen, Galliano, and Gaultier helped launched an extension of the gothic tradition in fashion in the 1990s. Gothic saw a reassurance in popularity again in the mid to late 2000s. Catherine Spooner writes, “In contemporary Western culture, the Gothic lurks in all sorts of unexpected corners. Like a malevolent virus, Gothic narratives have escaped the confines of literature and spread across disciplinary boundaries to infect all kinds of ideas, from fashion and advertising to the way contemporary events are constructed in mass culture.” (8) During the last few seasons, the gothic has once again started to lurk on the runways. The Fall/Winter 2023 Rodarte collection featured Siouxie of Siouxie and the Banshees-inspired eye makeup and endless long black lace dress — some of them fit with Victorian-inspired sleeves and black veils. Donatella Versace, too, took on the gothic for her Spring 2023 show titled “Dark Gothic Goddess.” While gothic has never disappeared and never will — a resurgence is only imminent.

Runway Links

Blumarine Fall/Winter 1998, Blumarine Spring/Summer 1993, Blumarine Fall/Winter 1997, Alexander McQueen Fall/Winter 2001, Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 2001, John Galliano Fall/Winter 2007, Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 2007, Alexander McQueen Fall/Winter 2008, Rodarte Spring/Summer 2023, Vaquera Spring 2020, Vaquera Fall 2022, Vaquera Spring 2022

Bibliography

Goodlad, Lauren M.E. and Michael Bibby. “Introduction.” In Goth: Undead Subculture, edited by Lauren M.E. Goodlad and Michael Bibby, 1-37. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007

Issitt, Micah L. Goths: A Guide to an American Subculture. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, 2011.

Montz, Amy L. “Fashion and the Female Gothic, Or, What to Wear to a House-Burning Party.” Women’s Studies 50, no. 7 (2021): 747–62. doi:10.1080/00497878.2021.1969930.

Spooner, Catherine. Contemporary Gothic. London: Reaktion, 2006.

Steele, Valerie, and Jennifer Park. Gothic: Dark Glamour. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Warwick, Alexandra. “Victorian Gothic.” In The Routledge Companion to Gothic, edited by Catherine Spooner and Emma McEvoy, 29-37. London: Routledge, 2007.