07: Unfolded: Department Stores, The Internet, and the Pursuit of Self Discovery

Before we could shop for identities online, there were department stores.

This essay is part of an ongoing series on The Pleat called Unfolded. Unfolded is a monthly historical essay on a topic of my choosing that touches on the intersection of consumerism, environmentalism, and fashion history.

At the department store, you can buy Chanel flats — they’re expensive but classic. Devon Lee Carlson has a pair. They’re Chanel. You could buy a pair from The Row, something sleek and minimalist and “quiet”. Or what about the Maison Margiela Tabi ones? All of the fashion girls wear them and they’re on sale on SSENSE. The Miu Miu ones that come with the ribbons are cute but they might already be out. Repetto is a good option, they’re sweet, coquettish, and a favorite of Brigitte Bardot, Kate Moss, Alexa Chung, and Lilly Rose Depp. Online, you could just buy a dupe or pick up a pair at Target or on Amazon. After all, they’re all just ballet flats, or are they? Someone will know and get it and someone won’t and that's the whole point.

There is no doubt that we are a culture obsessed with consumption. Long before we took to TikTok to share our Poshmark graveyard, our picks from TheRealReal, our latest pins, notes on our personal style, and everything we might buy during the SSENSE sale that never ends, there were department stores. In the age of online shopping and dying urban centers, department stores feel less relevant than ever but the history of department stores reveals the intimate relationship between our purchases and our identity within the emergence of mass consumer culture.

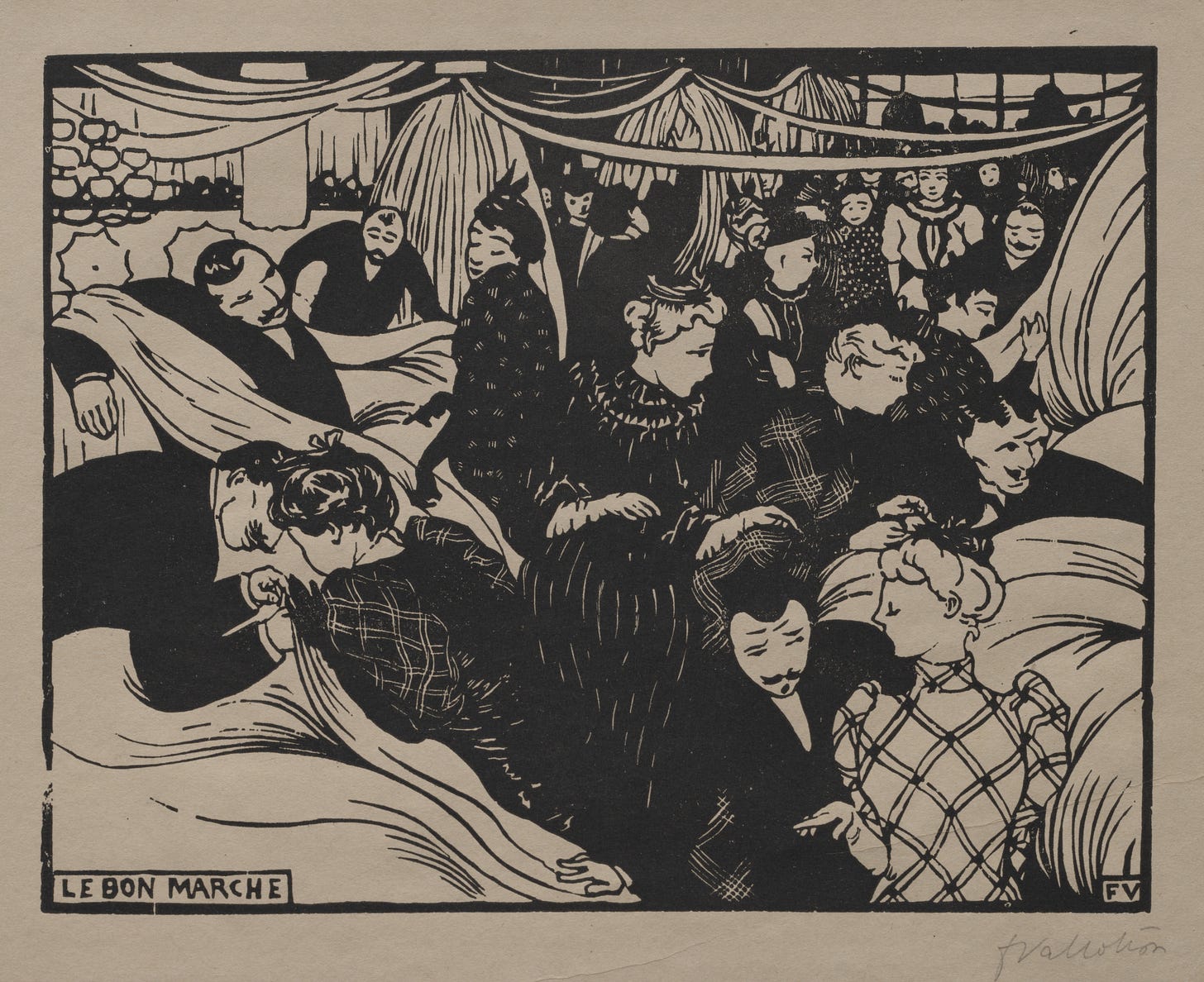

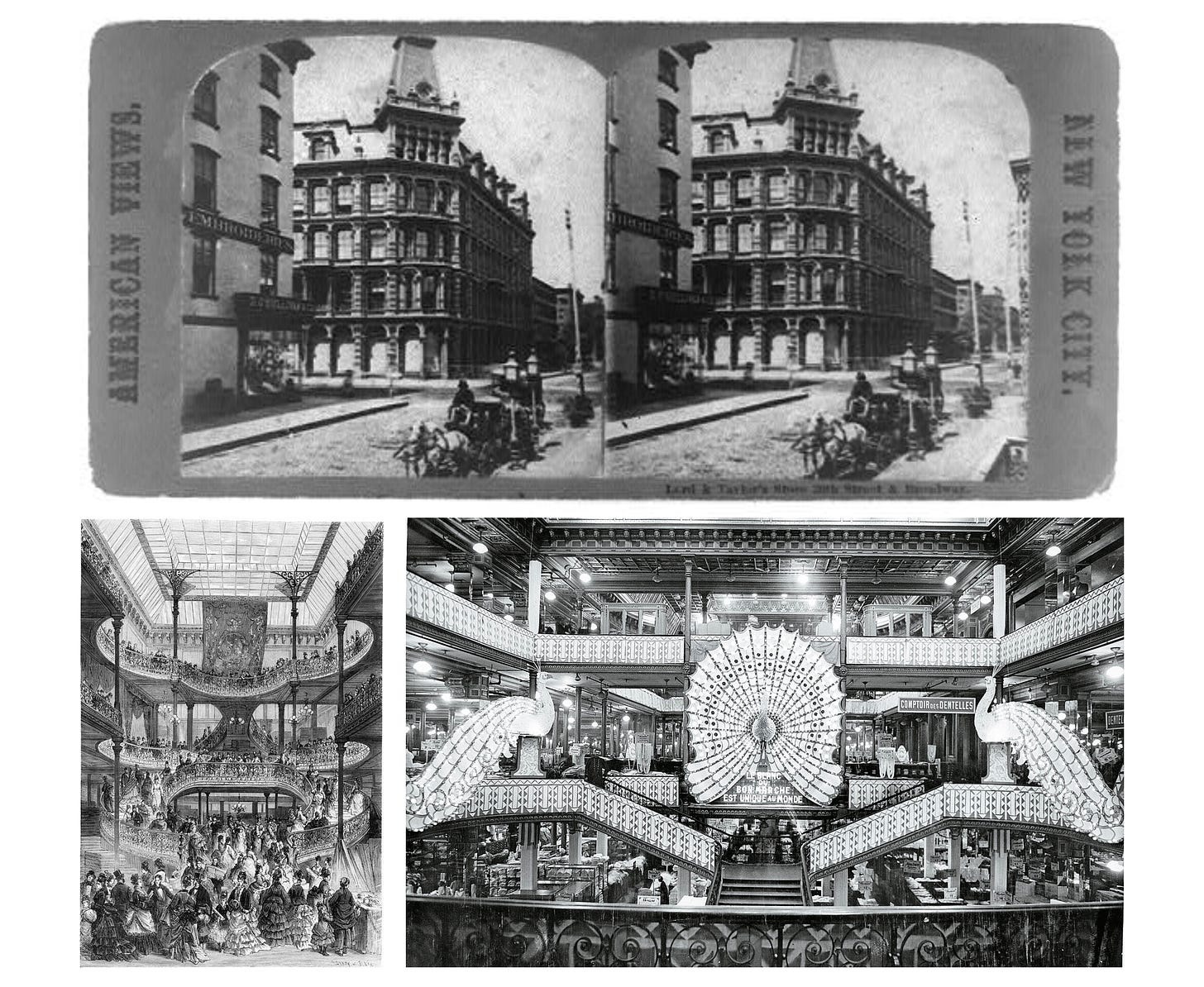

As a result of the advent of mass production in the mid to late 19th century, grand department stores began to dot cities on both sides of the Atlantic. The stores marked a departure from the small and separate specialty shops that dominated cities.1 They offered an unprecedented array of goods, all carefully arranged in a shiny spectacle. Quickly, these department stores redefined the shopping experience and revolutionized consumerism. Elaine S. Abelson aptly describes this transformation, “The links between production and consumption were clear. Needs multiplied because there was more to be had and an increasing standard of living that made more things feasible. Social identity was established through the new possibilities of consumption. If we substitute “want” for “need,” the nature of this critical change becomes apparent.”2 Department stores were not only a product of mass production, but they were the institutions that stood at the center of the changing economic landscape and made it the “success” it is now.

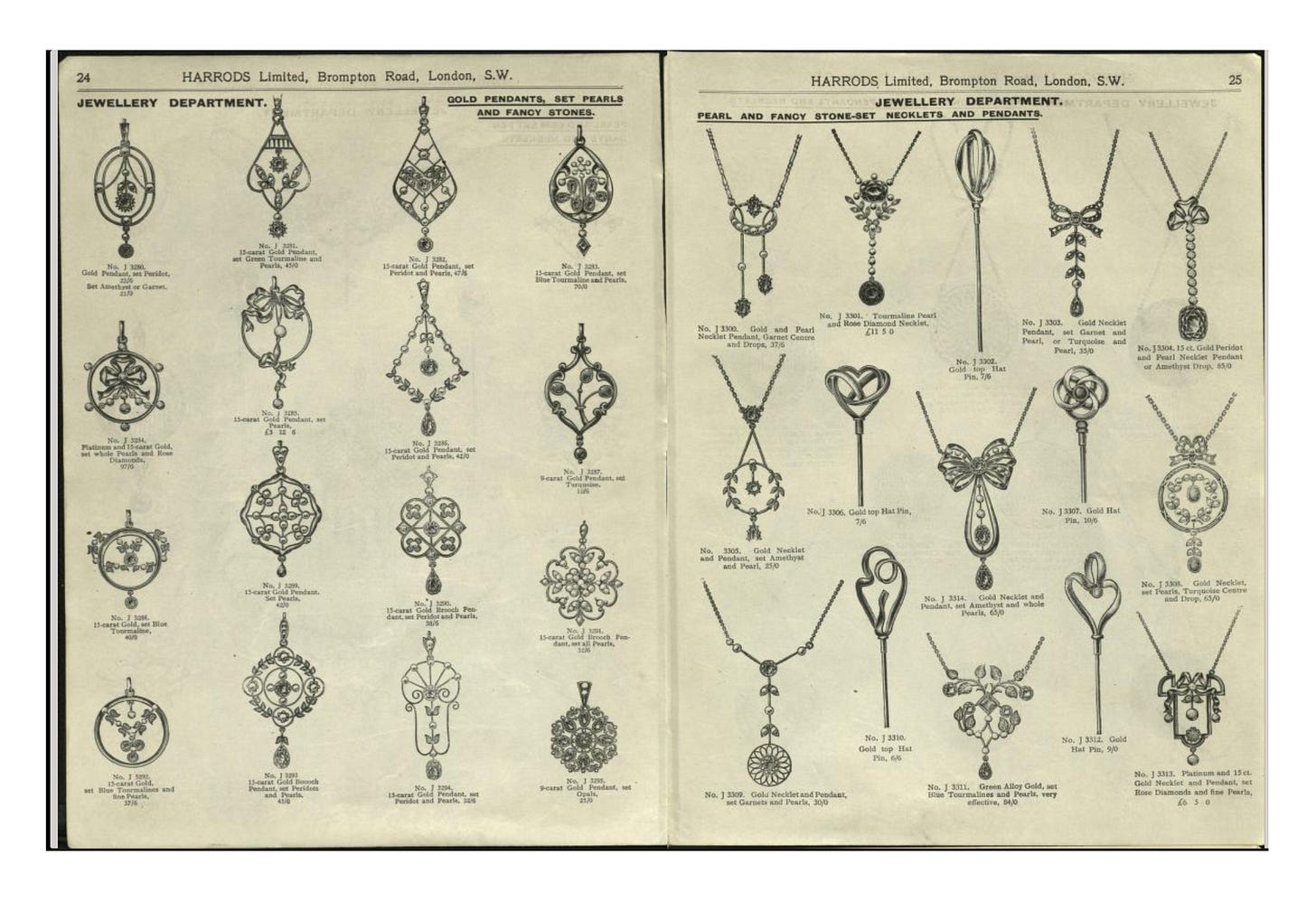

The success of the department store hinged largely on its marketing efforts. In the 1870s, when ready-to-wear clothing became a viable option, department stores were forced to persuade skeptical women that ready-to-wear clothing was not an indication of poverty. Upper and middle-class American women had historically made their own clothing and the few ready-to-wear options that did exist were for men in the military or people of lower incomes. As Abelson explains, the newspapers and advertisements “subtly denigrated the woman who sewed at home and made her feel old fashioned.”3 The first page of a Lord & Taylor catalog from 1870 stated, “Ready-made dresses are now a success– the troubles that have arisen in the past have all been overcome and anyone of ordinary figure can now be fitted perfectly.”4 Ready-to-wear, or mass-produced clothing became a symbol of modernity.

Knowing what to buy and where to wear it, too, became a symbol of progress and modernity. By the final decade of the 1800s, journals advised retailers that “the success of every dry goods department depends upon whether or not women can be taught that different costumes must be provided for different occasions.”5 Increasingly, it became commonplace for women to have clothing for different times of day and different occasions. It wasn’t enough to manufacture clothes quickly, in order to keep women buying, they had to manufacture new needs for clothes.

The stores not only revolutionized the fashion industry but also played a pivotal role in reshaping women’s identities. To sustain their stores, the owners manufactured the concept of newness and assigned it symbolic value. In 1896, a writer for the leading retail publication of the time, the Dry Goods Economist, wrote, “Any form of garment which permits the remodeling of clothes of previous seasons to conform to the new lines is ruinous to business!!” The writer continued, “Women must feel not to have new goods is to be far out of form.”6 Department stores themselves primarily advertised their merits in catalogs and advertisements in “ladies” newspapers. They went beyond mere product sales, promoting the idea that personal transformation and self-definition could be achieved through consumption. The stores actively shaped what these identities would ultimately look like.

Department stores emerged as a space that teetered the line between public and private. Historically, it had been a middle-class woman’s job to do the shopping but the site of the department store became both an extension of the home (a version of work) and a place of leisure.7 The department store can be viewed as an institution that not only shaped the essence of middle-class life but also redefined the concept of middle-class womanhood. In many ways, the department store served as a space where middle-class women could cultivate a sense of independence and identity. It was a space where they could venture without the need for male escorts, a place where they could bask in public enjoyment and make decisions independently. However, it is critical to recognize that this newfound independence was intrinsically intertwined with commerce.

In an era where we shop constantly and name new trends overnight, it is difficult to imagine a time when our identities were not tangled with our purchases. If the department store once functioned as a public space with seemingly unlimited possibilities for consumption, the internet has only done it better. The options online are more than comprehensible, more accessible, cheaper, the turnover is quicker and some of it will appear at your doorstep in less than a day. The convenience of a downtown destination meticulously stocked with everything imaginable has been replaced by the internet, which offers more than is imaginable. The spectacle of a shiny department store pales in comparison to what you can find at your fingertips in the never-ending stream of new content and new items to purchase.

The act of consumption, both in department stores over a hundred years ago and online today, serves as a distinct language for both differentiation and belonging. Abelson writes, “Consumption became a dynamic concept in which the perception of an object became as important as its intrinsic qualities. In the race to keep up with fashionable appearances, the satisfaction derived from goods often depended as much on consumption by others, as long as they were the “right” others, as on consumption by oneself.” It isn’t merely about acquiring new goods but also about the ever-evolving meanings we assign to our purchases. Our choices are not solely defined by the qualities of the products themselves but by how we and everyone else perceive them within the mechanism of fashion. It is the reason we buy something someone else has and the reason Alexa Chung wearing Repetto means anything to any of us. We look to tastemakers, to influencers, and to each other for permission for our purchases because whether we want to admit it or not, social validation plays a critical role in shaping our choices and by extension — our identities.

We all like to think taste is deeply personal. And there lies the paradox of personal style. Our tastes are intertwined in a vast system of everyone distinguishing themselves from one another, is that really as intimate of an act as we think it is? To have good taste means that someone else, or almost everyone else, has bad taste or at the very least, different taste.

Since the advent of mass production a century and a half ago, the technology for mass production has only become more available. In an estimation by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, in the last 15 years, worldwide clothing production has doubled while ‘clothing use’ has dropped approximately 40%.8 Trends are perpetually accelerated by the ease of production – it is abundantly clear that something has to give.

‘Personal style’ as it's lovingly referred to today on TikTok was forged in opposition to the culture of consumerism that department stores contributed to some a hundred years ago. Now, we tout personal style as the answer to all of our contemporary problems – to overconsumption, to our urgent need for sustainability, to navigating the relentless pace of fashion, and even to our own self-discovery. Personal style, too, is a language of its own, or perhaps more fittingly – it's a dialect. In many ways, the idea of personal style offers solace against the backdrop of the frenetic pace of fashion.

But personal style is susceptible to the same forces as the rest of fashion. Online, this is abundantly clear. I no longer have all the shoes I claimed I’d have forever. In a few years or maybe just a few months, the Chanel flats will be dated, The Row will be boring, the Tabis overdone and Repettos forgotten about. They’ll be something new to fawn over. Someone will still wear theirs and someone who assured themselves ballet flats are integral to who they are will have already sold them to Crossroads. In a system that feeds on our feelings of inadequacy, we must acknowledge how the forces behind the rampant pace of fashion influence our own understanding of ourselves. If done carefully, personal style is an opportunity to explore our identities outside of the forces that dictate trends – it offers a small path forward. But it is also imperative that we recognize that the answer to all of our contemporary problems does not lay solely in the purchases we make.

Susie Hennessy, “Consumption and Desire in "Au Bonheur Des Dames,” The French Review 81, no. 4 (2008): 697.

Elaine S. Abelson, When Ladies Go A-Thieving (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 25.

Abelson, When Ladies Go A-Thieving, 37.

Abelson, When Ladies Go A-Thieving, 24.

Abelson, When Ladies Go A-Thieving, 34.

Hennessy, “Consumption and Desire”, 698.

“Fashion and the Circular Economy: Deep Dive,” Ellen MacArthur Foundation, accessed September 27, 2013, https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/fashion-and-the-circular-economy-deep-dive#:~:text=Clothing%20represents%20more%20than%2060,has%20declined%20by%20almost%2040%25.