19: Elizabeth Hawes and A Century of Dupes and Copies

What does democratization in fashion really mean?

Welcome to The Pleat! This September, all newsletters will loosely engage with ideas around the sustainability of vintage. (Emphasis on loosely)

In the Summer of 1924, before her senior year at Vassar, Elizabeth Hawes worked as an unpaid apprentice at Bergdorf Goodman on the top floor in a hot sunlit room making made-to-order clothes for the chic women who bought them. Before she returned to school, the couture was delivered from France and she knew, that if she wanted to learn fashion, she had one option – Paris.

Fashion is an incredibly different system than it was 100 years ago when Elizabeth Hawes worked 11-hour days on the corner of 5th Avenue of 58th St or when she arrived in Paris in July the following year. 80% of the American wardrobe isn’t made in Manhattan. Clothes are less expensive. There are more options. There isn’t as centralized a taste-making authority. But one thing that hasn’t changed, is the tradition of dupes and copies.

Hawes was drawn to Paris for what she called ‘the French Legend’ — the unquestioned belief that France was the world’s foremost authority on fashion. The French fashion tradition was centuries old but in the United States, its superiority was upheld by magazines — Harper’s Bazaar upon its establishment in 1867, Vogue in 1892, and Women’s Wear Daily in 1910. There were a few attempts to establish the voice of American design, especially during WWI, but nothing stuck until the next World War.1 New York had businesses and manufacturers but Paris had artists and couturiers.

The French fashion tradition is rooted in centuries of skilled local artistry and craftsmanship. The 20th-century couturiers designed elaborate collections and created customs for their private clientele but most of their production was not done by them at all. The tradition of a twice-yearly fashion show started in 1910 in Paris — New York buyers and manufacturers sailed twice a year in August and February to attend the shows.2 They went to the showroom, saw the collection, and returned a few hours later to buy but they weren’t buying the clothes themselves, they were buying the rights to reproduce them.

When manufacturers and department stores bought the rights to reproduce a model, they took with them a combination of the following: a toile or cloth pattern of the garment which if returned within six months was not charged import fees, sketches, a reference sheet which outlined where to purchase the fabric, where to buy the clasps, closures and buttons and an agreement of how many copies they could legally produce. When they were done, they had an exact licensed replica of the garment.

For a high-end department store like Bergdorf’s or many trusted Seventh Avenue manufacturers, the high price tag of legal reproduction was worth it because it lent them the prestige of French fashion. In the mid-1930s, the reproduction of a single seasonal line, roughly thirty to seventy designs, could cost a manufacturer between $30,000 and $50,000 or about $500,000 today. The reproduction fee costs a corporate buyer between 30% and 40% of the original couture price tag.3 The steep price of legal reproduction was not worth it to everyone but it didn’t stop them from making reproductions.

Elizabeth Hawes started her job in Paris on August 15th, 1925, just in time for the new buying season. Except Hawes wasn’t working on behalf of a prestigious Manhattan department store, she was working as a sketcher at a copy-house. Copy houses were businesses that bought the important dresses from the important designers and recreated them for sale at lower price points. Each day, she went to work on St. Honore near Place Beauvais to create exact replicas of dresses by Jeanne Lanvin, Madeleine Vionnet, and Coco Chanel. They created identical replicas of couture pieces just like the ones at Bergdorf Goodman – same fabric, same wares, same embroidery. The only difference was that these copies were illegal.

To uphold the sanctity of French couture, French department stores and manufacturers were not allowed to buy the rights to reproduce garments like the American department stores. If you were in France, you were supposed to go directly to the source but most women couldn’t afford the originals so they bought from copy-houses. One estimation claims that in 1929, there were at least 100 copy houses in Paris.4 Another estimation puts the number of copy-houses somewhere between 200 and 500.5 Most of them were on side streets, on 2nd floors in dark studios where the garments were hidden away in case of a police raid.6 Instead of paying the steep overhead rights to replicate the garment, they relied on an elaborate network of shady activity for their copies.

There were countless ways copy houses attained the garments. Sometimes they hired couture seamstresses from the big houses to come in after hours and replicate what they spent the day working on. Sometimes a copy house paid her somewhere between $150 to $300 to sneak a garment out overnight. They’d pick it apart, make a pattern, and reassemble it before she had to sneak it back in the next morning. Sometimes they tried to hire top seamstresses and saleswomen outright so they could bring patterns, sketches, and their list of wealthy contacts. Sometimes wealthy women bought directly from the couture house but sent their new garments to a copy-house for “alterations” and in return, they’d get a few hundred back on their new purchase. There were women who allowed their new couture pieces to make a stop before delivery at a company that would loan pieces for a few hours. There were copy-houses that sent Americans like Elizabeth Hawes to the couture showroom to buy a piece for their mother only for them to change their minds a few hours later and return it after the copy houses had made a pattern and a sketch. There were model-renters – businesses that would buy patterns and toiles to rent out to copy houses for reproduction. There were manufacturers that would band together and each purchase a few toiles and share. The network of copyists extended all over Paris, and across the Atlantic, and grew more elaborate each season.

One of the most common schemes was sketching. After six months of sketching for the copy-house, Madame Ellis offered her a job sketching for an American manufacturer. Hawes accompanied the buyers to the collections at the prestigious houses, the buyers would nudge her gently when they wanted a model sketched. She’d study the garment diligently, remember every detail, and then hurry home to accurately sketch as many models as she could remember. According to Hawes 1 in every 8 women at the collections was a sketcher but the couture houses couldn’t risk falsely accusing an honorable client so they were rarely caught. A few hours later, Hawes and the buyer would return to the showroom. The buyer would order the items they wanted and Hawes would study the subjects of her sketches to ensure accuracy. Then the sketches boarded an express boat across the ocean every other day so the manufacturers could begin work before the new designs hit the department stores.

The journalist George Le Fevre estimated that in the late 1920s, the French couture business lost five hundred million French francs—or the equivalent of one billion dollars today—to the business of copying.7 The copyhouses were profitable because they didn’t pay the steep overhead rights to legally replicate garments and they flourished because women wanted to wear what was popular whether they could afford the real thing or not. Today, most copies are manufactured in China and Hong Kong and sold in places like Canal Street. Regardless of where the copies are purchased, the motivations remain remarkably similar – the status of luxury and the desire to belong. This era of fashion can be understood as a precursor to two modern phenomena: the prevalence of fake luxury goods and the trickle-down effect that drives fast fashion.

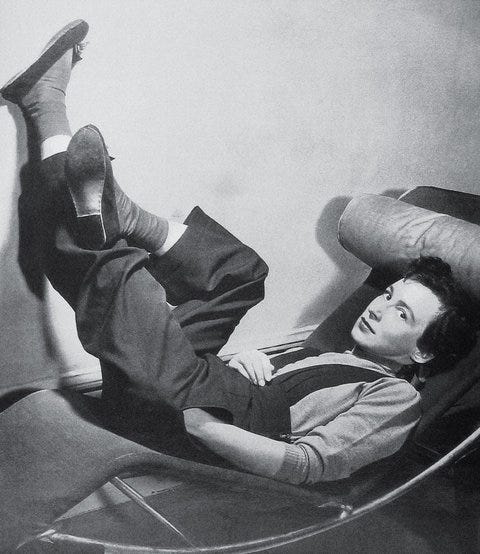

Elizabeth Hawes believed that every woman deserved to wear fabulous high-quality clothes and in 1928, she sailed back to New York in 1928 to start her eponymous label. By the time she returned to the United States, she had mostly abandoned her belief in ‘the French legend’. She designed for the American woman and she championed what, at the time, was a distinctly American democratic vision of fashion. In 1933, Hawes played with the idea of having a Seventh Avenue manufacturer mass-produce a collection of her designs. Hawes believed that all women should be able to wear well-designed, high-quality garments, regardless of their budget and she saw mass-manufacturing as a tool for her vision. But she was constantly frustrated by their work, they cut corners to save a few cents, used cheaper fabrics than she requested, and treated their workers terribly. She couldn’t bring herself to produce her work at the expense of workers’ lives and rights, and 7 years later, in 1940, tired of producing clothes for well-off women, she closed her studio on E 67th St.

Fashion is an incredibly different system than it was a century ago when Elizabeth Hawes was returning to her senior year at Vassar. The 1.7 trillion-dollar industry has outsourced most of its labor to low and middle-income countries where women and children produce garments at breakneck speed, under exploitative labor conditions, and in unsafe environments in the name of fashion. There are more clothes and they are cheaper than ever before. The promise of affordability is made possible by a labor force whose contributions are rendered invisible by a system that does not value them. The democratic vision of fashion that Hawes wanted was one she could not make a reality. Elizabeth Hawes is one of the defining voices of American fashion and her legacy offers a critical lens through which to consider how far we still have to go in achieving an equitable fashion system.

I have to ask – What would true fashion democratization look like?

FURTHER READING

A lot of this piece was inspired by Elizabeth Hawes’ Fashion is Spinach. Fashion Is Spinach was published by the American designer in 1938 and is THE book on the early years of American fashion. I can’t recommend it enough. AND YOU CAN READ IT FOR FREE ON ARCHIVE.ORG!

- wrote a fabulous piece on Canal Street titled “a tale of two canal streets”

“Inside the Delirious Rise of ‘Superfake’ Handbags” by Amy X. Wang is an incredible investigation into the world of fake luxury.

Leigh Bonwit discusses New York’s sticky fingers in a piece about Spring/Summer 2014 for DIS Magazine.

Max Meyer visited Paris 110 times between 1897 and 1929 as a buyer for the New York based manufacturer A. Beller & Co. A. Beller & Co. was one of the most respected suit and cloak manufacturers within the industry and their licensed couture copies were sold in high-end department stores. A few hundred of the thousands of couture sketches the company created are digitized online as part of the FIT SPARC collection.

A similar collection of couture sketches from Bergdorf Goodman are also digitized online as part of the FIT SPARC collection.

UPDATES

As part of this month’s series, I am creating a database of reader-recommended vintage stores. Any store, any city. If you have a suggestion, leave a comment or send me a message and I’ll add it to the database.

Do you want to be featured in The Pleat? I want to invite anyone who enjoyed this piece (or didn’t, whatever) to email me a photo of a piece of vintage that is important to you and reflect on why in a paragraph. Send me your stories! They will be published at the end of the month. Deadline is 9/24. sophdowlsocial@gmail.com

On Monday, September 9th, I hosted a closet sale on Instagram and am happy to announce that I donated $80 of the proceeds to Bushwick Ayuda Mutua.

Mary Stewart, “Wartime Marketing of Parisian Haute Couture in the United States, 1914–17,” in Fashion, Society, and the First World War, 17–28. Bloomsbury Publishing PlC, 2021.

Yuniya Kawamura, The Japanese Revolution in Paris Fashion, (New York: Berg, 2004), 61.

Véronique Pouillard, “Design Piracy in the Fashion Industries of Paris and New York in the Interwar Years,” Business History Review 85, no. 2 (2011): 324.

Pouillard, “Design Piracy in the Fashion Industries of Paris and New York in the Interwar Years,” 324.

Mary Lynn Stewart, “Copying and Copywriting,” in Dressing Modern Frenchwomen: Marketing Haute Couture, 1919-1939 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 121.

I didn’t talk in detail about the legality of copying and the institutional role of French organizations like the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture in preventing forgery because it would’ve made this essay several thousand words longer but if you are interested in reading more, I’d recommend Dressing Modern Frenchwomen: Marketing Haute Couture by Mary Lynn Stewart and The Japanese Revolution in Paris Fashion by Yuniya Kawamura for most context.

Pouillard, “Design Piracy in the Fashion Industries of Paris and New York in the Interwar Years,” 326.

Wow! This was such an informative and interesting read. I loved all the dirty details about how they would obtain and make copies of the garments.

Schiaparelli used to sell her knitting patterns to members of the public so they could make their own versions of her famous trompe de l’oeil knits!